Christian Taylor, Seattle, WA, December 2025

As I walked along the nearly empty road on my first full day in Al-Khalil, West Bank, Palestine, an unmarked truck full of armed young men wearing military fatigues slowly followed the walking pace of our small group, occasionally trying to provoke us by revving the engine and yelling out things that we couldn’t understand. I thought to myself, what am I doing here? Was it a mistake to come?

In November of 2024 I joined a delegation to the West Bank with Community Peacemaker Teams (CPT), along with my partner, Maria, and 3 other North Americans. CPT has been working in Palestine for 30 years and has a full-time team of locals there. They also have teams, at the invitation of local communities, in a few other places around the world where they confront systems of violence and oppression through accompaniment, observation, reporting, international advocacy, and solidarity networking.

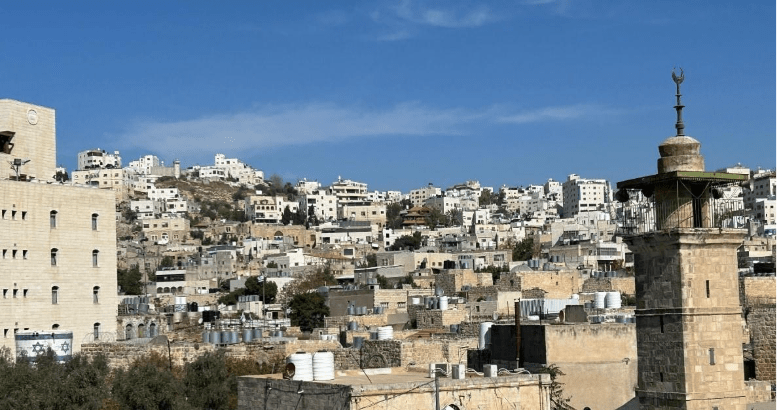

Rooftop view of a portion of Al-Khalil old city. Look closely, and you’ll find military watch towers and surveillance cameras.

During the 7-day delegation, the other delegates and I joined the full-time team in their day-to-day work of accompanying the local people in activities such as children crossing Israeli military checkpoints as they go to school and families harvesting olives. We observed the dehumanizing, apartheid conditions and documented instances of harassment. We also met with families, activists, and shop owners to hear their stories, wisdom, and hopes. After parting ways with the CPT team, we continued onward to Bethlehem and Jerusalem for three more days.

In the last two years, while we have seen 100+ years of colonization evolve into an ongoing genocide in Gaza, tensions have also been rising in the West Bank, where arbitrary arrests, land seizures, killings and other violence have increased.

My grandfather is Palestinian, making me one-quarter Palestinian. I’ve always known this, but I only learned anything about Palestine later in life, so I felt a strong pull to go to Palestine and discover these roots. I decided to go with CPT, rather than as a tourist, because I feel a strong call to stand up for oppressed people by taking direct action to confront systems of violence. However, before going on this delegation, I had many fears, doubts, and insecurities. Would I be safe from settler violence and from the IOF (Israeli Occupation Forces)? I don’t have any special skills; What impact can I really make? Will I be a burden on the local team? The problems are so big, and the impact I could make seems so small, so is it really worth the risk?

I was encouraged by the local team and some mentors that I didn’t need to “accomplish” anything; there is value in being there and seeing the situation with my own eyes. Witnessing the conditions would shape me, and I’d be able to share my firsthand experience with people back home. Being present in solidarity with the people would give them encouragement and strength to continue in their daily resistance.

In the rest of this post, I will take you through a summary of my experience. I will try to describe the overall atmosphere in the West Bank and daily reality for Palestinians living under occupation. I will also share stories and pictures from the delegation, including crossing and trying to cross checkpoints, harvesting olives, and Palestinians showing resiliency and joy amid daily harassment and threats of violence. Finally, I will share some of the personal and political lessons that I still carry with me today, one year later.

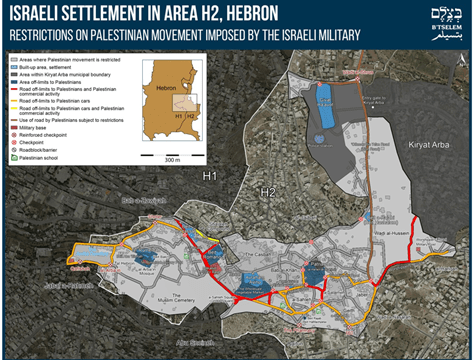

Map of the old city of Al-Khalil / Hebron

The delegation was based out of Al-Khalil (or Hebron), which is considered one of the oldest cities in the Levant and is the largest city in the West Bank. The city is home to the Ibrahimi Mosque / Cave of the Patriarchs where tradition holds that Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebecca, Jacob, and Leah are buried. It therefore holds religious significance in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Since the 1967 Six-Day War, the city has been under Israeli military occupation. It is a unique city because here the Israeli settlements are interspersed among the mostly Palestinian city. It is a microcosm of the occupation of the West Bank. Israeli settlements are illegal according to international law, however there is a blatant disregard of international law and Palestinians feel they have no one to turn to.

Imagine you are a Palestinian living in Al-Khalil. Chances are that any given day will be just fine. However, constantly under the surveillance of cameras, facial recognition software, and the gaze of soldiers from watch towers, you must always be alert to an ever-changing set of rules. If you are in an allowed area at the “wrong” time, wear the “wrong” clothes, walk on the “wrong” road, post the “wrong” thing on social media, gather with the “wrong” number of people, take a picture of the “wrong” place, or go through a checkpoint at the “wrong” time there is always the threat of arrest or violence (what is “wrong” depends on what an Israeli soldier or armed settler is feeling on that day, and is always subject to change).

If you display symbols of national pride or engage in peaceful protest or political organizing, you become a target for administrative detention: the practice of imprisonment without any charges or trial. Even if you and your family members don’t engage in these risky activities, you still worry for your relatives who may be arrested simply for committing the “crime” of being a young male.

This is the story of our friend whose two brothers have been in prison for almost two years under administrative detention with no charges. She hasn’t seen either of them or heard their voices. This is very common; every Palestinian knows someone with a story like this.

—

Street art depicting a fetus inside a womb of barbed wire, conveying the sense that Palestinians are born into a cage and never know anything else.

Walking through the city, I could feel and see the unrelenting harassment and the matrix of control. In some parts of the city, chain-link fences run above the streets, like a ceiling, installed to protect Palestinians from garbage and other objects thrown down by settlers who live above. This still doesn’t protect people from liquids which are thrown down. Some roads are reserved for Israeli settlers. On some streets, Palestinians have homes and are allowed to walk, but they are not allowed to drive. If a Palestinian living on one of these streets needs an ambulance in an emergency, a family member or neighbor must carry them to a different street where Palestinian cars are allowed to come.

There are 28 checkpoints throughout the city that people must cross to visit neighbors, shop for groceries, go to school, or go to the doctor. Going through these checkpoints made me feel like an animal in a cage. At best, it is a humiliating and time-consuming experience. But at any time, a difficult or moody guard could deny someone entry without cause, or the checkpoint could be closed entirely.

- Fence stopping garbage from being thrown down from settlements onto the street

- From the outside of a checkpoint.

- Men waiting in line to be let through a checkpoint.

One day on the delegation, our group attempted to cross a checkpoint to meet a local artist and activist who had prepared lunch for us. As we approached, a delegation leader pointed out a rubber bullet gun mounted at the checkpoint. Once inside the checkpoint, the soldiers started to ask us questions such as “what is your religion?”, and once they saw our U.S. passports: “who did you vote for in the election?” One soldier asked someone from our group for her phone. Legally, foreigners can’t be forced to have their phones searched. However, if we were to refuse, they could turn us away without giving any reason. We had all meticulously deleted photos, emails and messages from our phones that showed support for Palestinians. The solider looked at the phone for 5 seconds and then said, “you aren’t coming through here.” When we asked why, the only response he gave was “because I said so.” My best guess is that when the soldier saw that there were Palestinians in our group, he decided that he wouldn’t be letting any of us through.

It was disappointing to not be allowed through the checkpoint, but even more disheartening was the fact that the CPT partner had prepared us a meal and we were unable to receive her hospitality. This lack of ability to reliably make plans is a constant reality for Palestinians living under occupation. Afterwards, one of the CPT staff told us “Trying is part of the process. Sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn’t, but we keep trying. It is part of the journey to freedom and justice.”

In addition to the permanent checkpoints, roadblocks are sometimes put up overnight and stay indefinitely. What used to be a one-minute walk between relatives’ houses now might take thirty minutes to circumnavigate closed roads.

The man on the other side of the fence was so close, but because this road has been closed, it would have taken 30 minutes to get to where he was

Israeli authorities control where and what Palestinians can build. Israeli settlement buildings are more modern, as over 95% of building permits for Palestinians are denied. Water utilities are separate, so while Israeli settlements get running water 24/7, Palestinians only occasionally get water and must store it in tanks on the roof. Palestinians also must get permission to go to their agricultural land, which might only be granted once per year.

All of this control is not for the stated purpose of “security”. There are usually ways around the road obstructions for people who are willing to undergo severe inconvenience. Palestinians and international human rights activists say that the checkpoints, obstructions, and constant harassment exist to make daily life difficult for people and to destroy the economy so that people will give up and leave, allowing Israel to take over more land while claiming that they didn’t steal it.

We saw Palestinian homes and land that had been taken over by settlers. One school that we saw has had its playground turned into parking lots for settlers. The playground for the kids is now a very small outdoor area with a cage around it.

- We spent a day helping a family with olive harvest. An important event both economically and culturally

- Before long, soldiers started to gather and watch us picking olives. They started to buzz drones near our heads, causing the family and our delegation to pack up and leave for the day.

Despite everything, the Palestinian people are full of love and life. Walking the narrow streets of the old city, we were invited into neighbors’ homes and shops for coffee. Small children shyly practiced their English and gave out handshakes. Random passersby greeted us and welcomed us to Al-Khalil. There is a vibrant art scene as people find a way to express themselves.

In a post on our blog, my partner, Maria wrote about how one CPTer “cheerfully recounted a time she was on the rooftop when a drone descended nearby, and a voice started talking to her and demanding that she leave the area. She was laughing at the idea of some young guy sitting up in a tower and playing with the drone like a videogame, and at the audacity of that demand. The unrelenting demands, incessant questions, and arbitrary and changing sets of rules are designed to create a sense of powerlessness and humiliation. But how preposterous to think the Palestinian people could be broken.”

As another CPTer said, “We are Palestinian. Day after day we become more strong . . . No one else in the world can live like this.”

One of the days, we had coffee with an elderly woman whose house is right next to an Israeli checkpoint. Her family has been in this house since her grandfather’s time, and she now lives there alone. She’s had soldiers pee on her property. She’s had sound bombs thrown at her house. She isn’t permitted to leave her house at night or on certain days of the week. The soldiers call her names and harass her. They play loud music all night to disturb her sleep. After recounting all of this to us, someone from our group asked her how she had such a big smile on her face the whole time we were with her. She told us: “Thank God for everything. I am still alive. Why would I not smile?”

We saw this attitude in many Palestinians that we met. When I feel low on hope and lack the resolve to continue the struggle, I think about meeting Bader.

Bader owns a shop on the main commercial street of the Old City of Al-Khalil. We stood with Bader in his shop during the Saturday “settler incursion” into the old city, where each week a group of settlers, accompanied by a large contingent of heavily armed soldiers, parade through the city with a guide telling them about why the city is rightfully theirs.

As they go through the city, soldiers force shopkeepers to close their shops, and stop people from moving across the city. It is common for there to be verbal harassment, vandalism, and sometimes physical altercations. Bader goes through this every week. Yet he keeps his shop open knowing that he will not sell anything, and despite past incidents when settlers have broken his goods. He is doing this as an act of resistance. He will smile and have joy as an act of defiance. He will continue to offer hospitality to strangers and foreigners, an important part of Arab culture you encounter while traveling in the region. He refuses to let the settlers determine how he will live his life or define his value.

A young relative of Bader’s standing at the front of the shop while the group of settlers and soldiers pass by.

As the “tour group” approached our area of the city, we stood at the front of Bader’s shop ready to document any incidents. First, we saw a group of about 20 soldiers come through clearing the way and making people move off the street. One of the soldiers came over to us and forced us to step back inside the shop. It felt like we were cattle being herded. Behind the soldiers came a group of about 100 settlers. Pointing, laughing, taking in the sights, and mocking the people waiting to get back to their daily life. Some of them saw us and pointed and yelled “Americans!”

Maria wrote how “this wasn’t a tour; it was a safari; the visitors having stepped into the jungle to gawk at wild animals. Confident in the knowledge that if any of the animals turned threatening, their armed guards were there to put it down. In the face of this, I felt my animal nature rise to the surface in a visceral way. My heart racing, body trembling in the presence of a hostile power with no concept of my humanity.”

But Palestinians refuse to become animals. Bader stepped out in front of us, standing tall and full of dignity, ready to welcome any customers, who he knew would not come.

This is the Palestinian value of sumud, or steadfast perseverance. It is a refusal to disappear, because existence is resistance. It is finding beauty and joy amid struggle as an act of defiance.

Bader refusing to take any money for something that I wanted to buy from his shop.

While sumud is a beautiful value and political strategy, and we can all learn something from it, it is important for those of us in Western countries to remember that our privileges come from the status quo of colonialism and neo-colonialism. For us, to exist in privilege is not resistance. We heard from many people that they will continue to resist however they can, but that powerful Western countries have been complicit in Israel’s occupation, and it will take international pressure from these countries for the occupation to end. Our resistance must take an active form, so that while our Palestinian brothers and sisters continue to persevere, we play our part in mobilizing our communities to pressure international institutions and corporations to force an end to Israeli occupation and apartheid.

- Street art saying “congress must stop funding Israeli apartheid”

- Tear gas canister from Ayda refugee camp, the most tear-gassed place in the world, that says “Made in U.S.A.”

Looking back now on that first day in Al-Khalil when I was wondering if it was a mistake for me to be there, I can now unequivocally say that no, it was not a mistake. It has been one of the most impactful experiences of my life.

I don’t know if I had any tangible impact while there, but it was incredibly meaningful. The level of oppression that I saw broke my heart in a way that will forever change the way that I see the world. The spirit of resilience that I saw in people instilled in me a determination to stand with people facing oppression. The people I met told me that knowing they have the support of people around the world helps them to keep going in the face of daily oppression.

By sharing our experiences since returning home, Maria and I have been able to help friends and family understand what daily existence in Palestine is like. As most of the Palestinian activists that we met told us: sharing with people back home is more important than what we can do on the ground in Palestine, since it is the western governments, and especially both parties of the United States government, which give the weapons and the political cover for Israel to continue their occupation, human rights abuses, and every few years their mass atrocities.

When having conversations about the delegation experience, very often questions come up about Israelis and Palestinians reconciling their differences and making peace. These questions come from a well-intentioned place. However, I believe they indicate a misunderstanding about the root of the issue. Reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians is good to talk about, but I believe that an over emphasis on it indicates an incorrect understanding of the issue as a conflict between two sides rather than understanding the issue as an ongoing colonial occupation.

Before there can be peace there must be liberation and justice. It will take an end to the occupation for room to be opened up for true reconciliation. Seeing the issue as an ongoing colonial occupation rather than a “conflict” is important for anyone in the international community, because it shifts the focus from making peace through reconciliation to a focus on using international pressure to dismantle the occupation so that there can be peace and reconciliation.

Talking with Palestinians, I heard often about how they want peace, but that for true peace to be made, the systemic issues must first be addressed. I also learned from these people about how they see the same system of colonial, racial capitalism at the root of their oppression, and at the root of other oppression around the world. They see liberation struggles around the world as interconnected.

Art on the separation wall near Bethlehem including a mural of George Floyd

I think this is an important lesson for any of us who care about peace and justice. We all have certain causes that we are most deeply connected to, and we don’t have capacity to do everything. However, there is a danger if we essentialize one cause without recognizing that the same structures are also behind different oppressions. Gaining “equality” for one group without addressing the extractive capitalist system that relies on exploitation, will just mean that someone else is now being oppressed. So, we need to see the interconnectedness behind different struggles and address the systems that are behind them all.

One activist told us: some day the occupation will end, and when it does we will find another just cause to support, because no one is truly free until everyone is free.

Another activist we met told us: as Palestinians, we have a short rope around our neck, and we can see who is controlling it. Everyone else has a rope around their neck as well, but it is long and they don’t know who controls it, or even recognize that it is there.

It is easy these days to find a variety of ways you can support the movement for the liberation of Palestine. As I wrap up, I will just suggest these few for you to consider, informed by my delegation to Palestine:

- Get involved in Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaigns in your local area. This is our most important tool of international pressure and takes many different forms (meaning everyone can find something that is suited to them). It could be petitioning legislatures for sanctions, picketing BDS target companies, pressuring your school or union to divest funds, or many more things including more disruptive direct actions. There are likely already BDS campaigns in your area that you can join.

- Visit Palestine. There are many ways to visit that carry more or less risk. Showing your solidarity by walking alongside Palestinians is powerful, and it is logistically possible for more people than you might think. Seeing the land and meeting the people is a powerful experience that will shape you and will give you more authority to talk about Palestine with confidence and experience back home.

- Donate to Community Peacemaker Teams

Christian is a software engineer, activist, outdoor and travel enthusiast, and home cook, based in Seattle, Washinton, USA. Christian and his partner, Maria, write occasional blogs about their experience traveling and volunteering on their Substack.